Unfinished Pyramid

Zawyet el-Aryan is an ancient Egyptian necropolis dating to the Third and Fourth Dynasties of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2494 BCE), situated between the Giza plateau and Saqqara in the Memphite necropolis region.

The site's primary monuments consist of two unfinished pyramids: the southern Layer Pyramid, likely built for Pharaoh Khaba (c. 2670 BCE), which features a step-like structure of five layers rising to an intended height of about 45 meters without an outer casing, and the northern Unfinished Pyramid, provisionally attributed to a Fourth Dynasty king such as Baka (alternative names Nebka or Huni), planned on a base of 200 by 200 meters with a deep 21-meter subterranean burial pit but lacking any superstructure.

Associated with these pyramids are mastaba tombs of high officials, reflecting the site's role as a royal and elite burial ground that demonstrates transitional experimentation in pyramid architecture from stacked mastabas to more complex forms.

Archaeological attribution remains tentative due to the unfinished state and limited inscriptions, with the Layer Pyramid's builder inferred from artifacts in a nearby mastaba and the northern pyramid's from stylistic comparisons and fragmentary hieratic graffiti.

Since the 1960s, the site has been within a restricted military zone, limiting further systematic excavation and contributing to ongoing debates about its full extent and purpose.

Geographical and Historical Context

Location and Environmental Setting

Zawyet el-Aryan is situated in the Giza Governorate of Egypt, on the western desert plateau bordering the Nile Valley, approximately 5 kilometers south of the Giza pyramid complex. The site occupies an intermediate position in the Memphite necropolis belt, roughly 7 kilometers north of Saqqara and between the major pyramid fields of Giza to the north and Abusir to the south.

The terrain consists of elevated limestone bedrock rising about 60 meters above sea level, overlooking the Nile River to the east, with ancient Memphis positioned directly across the floodplain. This strategic location facilitated access to quarried stone from local Eocene limestone formations while providing proximity to the Nile for transporting heavier materials like granite from Aswan.

The terrain consists of elevated limestone bedrock rising about 60 meters above sea level, overlooking the Nile River to the east, with ancient Memphis positioned directly across the floodplain. This strategic location facilitated access to quarried stone from local Eocene limestone formations while providing proximity to the Nile for transporting heavier materials like granite from Aswan.

Environmentally, the area exemplifies the hyper-arid conditions of Egypt's Western Desert margin, with negligible rainfall and reliance on the adjacent Nile floodplain for sustaining construction labor and resources during the Old Kingdom period (c. 2686–2181 BCE). The site's bedrock, primarily nummulitic limestone, was directly exploited for pyramid bases and subterranean chambers, underscoring the geological suitability of the plateau for monumental architecture.

Role in Old Kingdom Pyramid Building Tradition

The Layer Pyramid, constructed during the Third Dynasty (c. 2686–2613 BCE) and often attributed to Pharaoh Khaba (r. c. 2670 BCE), represents an early example of step pyramid architecture in the Memphite necropolis, built using an accretion layer technique that involved stacking horizontal layers of limestone blocks to form a core of approximately five to seven steps. This method, visible in the pyramid's ruined state, reflects the incremental building practices that followed Djoser's Step Pyramid at Saqqara but introduced variations such as a more compact layout and anomalous substructural elements, including debated shaft depths (e.g., 9.5 meters for certain galleries) and a burial chamber of consistent dimensions across excavations. These features contributed to the Third Dynasty's experimentation with vertical monumentality, transitioning from elongated mastabas to multi-layered superstructures while maintaining subterranean access for royal interment.

The site's Unfinished Northern Pyramid, dated to the Fourth Dynasty (2613–2494 BCE) and potentially commissioned by King Bakare (also read as Nebka or Bikheris), further illustrates the Old Kingdom's pyramid-building escalation, with a planned base measuring 200 by 200 meters and an intended slope of about 52 degrees, rivaling the scale of later Giza monuments. Its substructure—a 21-meter-deep pit hewn directly into bedrock, similar to Djedefre's innovative design at Abu Rawash—demonstrates advancements in quarrying and burial security before superstructure erection, though the project's abandonment left only foundational trenches and an enclosure wall of 665 by 420 meters. This unfinished state highlights potential disruptions in royal succession or resource allocation, yet the design's true pyramidal inclination signals a shift from Third Dynasty steps toward the smooth-sided forms epitomized by Sneferu's and Khufu's pyramids.

Collectively, Zawyet el-Aryan's monuments positioned the site as a secondary necropolis between Saqqara and Giza, evidencing the Third and early Fourth Dynasties' proliferation of pyramid fields and iterative refinements in scale, materials (local limestone and granite), and engineering—such as bedrock integration—to symbolize pharaonic power and eternal ascent. The Layer Pyramid's stepped form and the Northern Pyramid's aborted true pyramid intent underscore causal factors in architectural evolution, including trial-and-error in load-bearing layers and subterranean stability, amid the Old Kingdom's centralized state-driven labor mobilization of tens of thousands for these enduring symbols of divine kingship.

Discovery and Archaeological Investigations

Initial European Explorations (19th Century)

In 1837, British army officer Richard William Howard Vyse, in collaboration with engineer John Shae Perring, conducted initial surveys of the pyramid field at Zawyet El Aryan, producing plans of the Layer Pyramid and the Unfinished Northern Pyramid as part of broader explorations of Old Kingdom monuments south of Giza. These efforts marked the first systematic European documentation of the site's core structures, focusing on surface measurements and basic architectural observations rather than excavation.

Perring returned in 1839 for a targeted examination of the Layer Pyramid, noting its stepped form and partial masonry remnants while clearing debris from the entrance to access the descending corridor leading to the burial chamber. His work provided the earliest detailed descriptions of the pyramid's superstructure, estimating its original height at approximately 42 meters based on surviving layers, though he conducted no extensive subsurface probing at that time.

The Unfinished Northern Pyramid received similar preliminary attention from Perring in 1837, who recorded its massive substructure pit—measuring about 200 meters on each side and over 20 meters deep—along with rudimentary casing blocks at the base, highlighting its aborted construction phase. These 19th-century initiatives, driven by private initiative amid limited institutional support, laid foundational cartographic and descriptive records but yielded few artifacts, as efforts prioritized mapping over intrusive digs. German expeditions under Karl Richard Lepsius in the 1840s later referenced these pyramids in passing during their comprehensive Egyptian survey, assigning the Layer Pyramid the designation "Pyramid VIII" without adding significant fieldwork.

Systematic Excavations and Key Findings (Late 19th to Mid-20th Century)

In 1896, French Egyptologist Jacques de Morgan conducted excavations on the Layer Pyramid, uncovering its subterranean features including a descending corridor leading to an unfinished burial chamber approximately 10 meters below the surface, though no royal burial or significant artifacts were found. These works revealed the pyramid's stepped structure composed of horizontal layers of limestone blocks, with estimates of its original height varying between 17 and 30 meters due to erosion and incomplete documentation.

Systematic investigations intensified in the early 20th century under Italian archaeologist Alessandro Barsanti, who focused on the Unfinished Northern Pyramid from 1904 to 1905 and resumed briefly in 1911–1912. Barsanti's team cleared a deep vertical shaft descending over 30 meters into the bedrock, revealing a T-shaped subterranean complex with smoothed walls and a basal chamber containing an oval limestone sarcophagus carved from a single block, though it yielded no human remains or grave goods. The excavation also exposed an adjacent sloping trench and preparatory platforms, indicating advanced quarrying techniques but abandonment prior to superstructure completion, halting further progress due to World War I and Barsanti's death in 1917.

Concurrent efforts in the site's necropolis uncovered several large mastaba tombs dating to the Third Dynasty, including elite burials with limited inscriptions attributing them to officials associated with pyramid construction, though systematic artifact recovery was sparse and primarily consisted of pottery fragments and tools. These findings underscored Zawyet El Aryan's role as a secondary pyramid-building center, with architectural anomalies like the Layer Pyramid's accretive layering suggesting experimental phases in Old Kingdom design, yet the absence of definitive royal attributions highlighted interpretive challenges amid incomplete records.

Cessation of Work and Institutional Barriers

Excavations at Zawyet El Aryan faced initial interruptions during the early 20th century, particularly under Alessandro Barsanti's work on the Unfinished Northern Pyramid starting in 1905, which was halted by World War I and his death in 1917. Limited post-war efforts occurred sporadically, but comprehensive archaeological investigation ceased entirely in 1964 when the Egyptian military designated the site a restricted zone.

This military lockdown, enforced by the Egyptian government, prohibits all modern excavations, surveys, and public access, rendering the site's pyramids and necropolis inaccessible for scholarly study. The surrounding necropolis has been overbuilt with military structures, including bungalows, further complicating preservation and investigation.

Institutional barriers stem from Egypt's centralized control over antiquities, managed through the Ministry of Antiquities (formerly the Supreme Council of Antiquities), which prioritizes national security over archaeological access in militarily sensitive areas near Giza. Permit requirements are stringent, often denied for foreign teams, and bureaucratic delays or outright refusals reflect broader geopolitical concerns, including proximity to key infrastructure and historical precedents of site militarization during conflicts like the Arab-Israeli wars. This has left unresolved questions about the site's subterranean features and pyramid attributions unexamined with contemporary methods such as geophysical scanning or DNA analysis of remains.

Primary Monuments

Layer Pyramid: Structure and Attribution

The Layer Pyramid, located south of the Unfinished Northern Pyramid at Zawyet el-Aryan, consists of a core superstructure built using the accretion layer technique, wherein horizontal bands of limestone masonry slope inward at an angle of approximately 68 degrees, forming rudimentary steps. This method employed roughly 14 distinct accretion layers, suggesting an intended design of five to seven steps, though the monument remains heavily eroded and incomplete, with only the basal portions of the lowest step preserved. The square base measures about 84 meters per side, while the estimated original height reached around 40 meters, constructed from local limestone without evidence of casing stones.

The substructure includes a descending corridor leading to a rectangular burial chamber carved into the bedrock, measuring 3.63 meters in length, 2.65 meters in width, and 3.0 meters in height, accessed via a blocking plug system similar to that in Sekhemkhet's pyramid at Saqqara. Italian Egyptologist Alessandro Barsanti excavated the site between 1900 and 1905, uncovering no artifacts, inscriptions, or remains of a burial, which has fueled speculation about whether the pyramid was ever completed or used.

Attribution of the Layer Pyramid to Pharaoh Khaba of the Third Dynasty (c. 2640–2637 BC) relies on indirect evidence: stone vessels bearing Khaba's Horus name (Hor-Khaba) were found in the adjacent Mastaba Z500, interpreted as contemporary due to architectural and chronological similarities, though no cartouches or dedications appear on the pyramid itself. This association, first proposed in early 20th-century scholarship and upheld by Egyptologists like Miroslav Verner, positions the structure as a transitional step pyramid following Djoser's innovations but preceding true pyramids, yet the absence of on-site confirmation leaves room for alternative attributions to unnamed rulers of the period.

Unfinished Northern Pyramid: Design and Subterranean Features

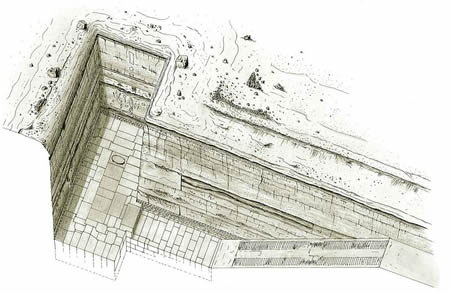

The Unfinished Northern Pyramid at Zawyet El Aryan comprises a vast rectangular pit excavated directly into the natural limestone bedrock, forming the core of its substructure without any overlying superstructure or casing stones beyond the initial groundwork. The base measures approximately 200 meters by 200 meters, suggesting an intended scale comparable to major Old Kingdom pyramids, though no evidence of started perimeter walls or core masonry survives above ground level. This design aligns with transitional pyramid architecture of the late 3rd or early 4th Dynasty, where deep shafts preceded the erection of stepped or true pyramid forms, but construction halted after bedrock preparation, leaving the site as a "great pit" rather than a partially built monument.

Subterranean features center on a T-shaped burial complex accessed via a steep descending stairway featuring a horizontal landing midway down, leading to a main north-south passage that branches into an east-west oriented chamber. The burial chamber itself remains incomplete, with precisely cut smooth walls but no ceiling slabs or finished sarcophagus enclosure, indicative of work abandoned mid-excavation. Floor construction incorporated massive granite blocks, each estimated at 9 tons, into which an oval sarcophagus pit was hewn—measuring 3.15 meters in length, 2.22 meters in width, and 1.50 meters in depth—sealed originally with a lid and containing traces of human remains, though these were subsequently lost or unpreserved.

Excavations conducted by Alessandro Barsanti from 1900 to 1905 under the Egyptian Antiquities Service revealed these elements but were criticized for incomplete documentation and unscientific methods, including potential damage to architectural features; no significant artifacts beyond the sarcophagus traces were reported, and claims of a dedication tablet inscribed with the name of Djedefre lack corroboration from preserved records. The pit's depth reaches roughly 20-30 meters in places, with vertical shafts possibly intended for blocking or ventilation, though unfinished states prevent full interpretation of access mechanisms or security features common in contemporaneous pyramids like those at Giza. Overall, the subterranean layout reflects standard Old Kingdom burial engineering—prioritizing isolation and grandeur—but its truncation underscores causal factors like resource shortages or royal death interrupting projects, without evidence of ritual repurposing or alternative functions such as a temple.

Necropolis and Associated Remains

Mastaba Tombs and Elite Burials

The necropolis surrounding the pyramid complexes at Zawyet el-Aryan encompasses five cemeteries spanning the First Dynasty through the Roman Period, with mastaba tombs concentrated in areas linked to Third Dynasty activity. These rectangular, flat-roofed structures, constructed primarily of mudbrick with occasional stone elements, served as elite tombs for high-ranking officials, courtiers, and potentially royal relatives associated with the pyramid builders. Unlike more extensively explored sites such as Saqqara, the mastabas at Zawyet el-Aryan exhibit typical Old Kingdom features, including subterranean burial chambers accessed via shafts and surface superstructures for cultic offerings, though specific architectural variations remain poorly documented due to incomplete surveys.

Excavations in the early 20th century identified several large mastabas near the pyramids, but yielded minimal artifacts or inscriptions, suggesting either looting in antiquity or abandonment before full utilization. No comprehensive burial assemblages—such as sarcophagi, funerary goods, or titled individuals—have been systematically reported from these tombs, contrasting with richer finds at contemporary necropolises. For the Layer Pyramid, surveys indicate an absence of adjacent mastaba fields, implying limited elite interments or later overbuilding.

Military restrictions imposed since 1964 have halted further work, overbuilding parts of the necropolis with modern structures and preventing detailed mapping or clearance of these elite burial zones. This has perpetuated uncertainties about the social hierarchy reflected in the mastabas, including the identities and roles of the deceased in the pyramid construction hierarchy. Empirical evidence from surface reconnaissance underscores their role in the broader funerary landscape, yet underscores the site's under-explored status relative to peer institutions.

Funerary Artifacts and Inscriptions

Mastaba Z500, located approximately 200 meters from the Layer Pyramid, yielded eight alabaster vessels inscribed with the Horus name of Khaba, a 3rd Dynasty pharaoh, during excavations in the early 20th century. These stone vessels represent the primary funerary artifacts associated with the site's elite burials, suggesting reuse or dedication to non-royal tomb owners linked to royal patronage. No mummies, sarcophagi, or additional grave goods such as jewelry, ushabtis, or furniture have been documented from this or other mastabas, consistent with reports of absent burial traces in the pyramids themselves.

The necropolis features five mastaba cemeteries, with only the late 3rd Dynasty group containing larger mudbrick tombs, including four substantial mastabas explored by George Reisner and Clarence Fisher around 1910. Their work uncovered structural details but no significant artifacts beyond incidental finds like the Khaba vessels, attributed to the tombs' plundering or incomplete investigation. Reisner and Fisher noted that these mastabas likely belonged to officials or family members contemporary with the pyramid builders, yet empirical evidence for elaborate funerary assemblages remains scant.

Inscriptions at Zawyet el-Aryan are predominantly construction-related graffiti rather than funerary texts. In the Unfinished Northern Pyramid's substructure, Italian archaeologist Alessandro Barsanti recorded at least 67 ink inscriptions in black and red during 1904–1905 excavations, detailing workmen's gang names (e.g., "Seba-weref-ka" for the necropolis), quarrying marks, and debated royal cartouches possibly reading "Bikheris" or variants. Fragmentary hieroglyphs appear elsewhere, but none constitute offering formulas, biographical stelae, or afterlife invocations typical of Old Kingdom tombs. The absence of verifiable funerary epigraphy underscores the site's emphasis on monumental architecture over documented elite commemoration, with later military restrictions preventing further recovery or analysis.

Construction Techniques and Architectural Analysis

Materials, Tool Marks, and Engineering

The Layer Pyramid and Unfinished Northern Pyramid at Zawyet El Aryan were constructed primarily from limestone blocks quarried from local sites, including the nearby Zawyet el-Aryan limestone quarry complex. This material choice aligns with 3rd Dynasty practices, where readily available nummulitic limestone facilitated large-scale masonry without extensive transport. The Layer Pyramid's core exemplifies an accretion-layer technique, with ashlar blocks laid in horizontal courses to form distinct steps, a method that allowed incremental height gains while maintaining structural stability through interlocking layers.

Engineering features reveal early experimentation with subterranean architecture. The Unfinished Northern Pyramid's burial chamber was excavated as a 21-meter-deep vertical shaft into natural bedrock, a technique akin to contemporary pits at Abu Rawash, requiring precise leveling and support to prevent collapse during construction. Surface alignments and enclosure walls measuring approximately 665 by 420 meters demonstrate planning for a true pyramid superstructure, potentially rising to heights comparable to later Giza monuments, though abandoned before completion.

Tool marks on exposed quarried surfaces and unfinished bedrock at the site, including those in the local quarry, exhibit striations and facets consistent with manual extraction using pick-mattocks and chisels, tools hardened with arsenic-alloyed copper prevalent in the Old Kingdom. These marks, observed in haphazard extraction zones, indicate labor-intensive pounding and wedging rather than mechanized cutting, with periodic sharpening evident from interrupted grooves—evidence corroborated by comparative analyses of period quarries. No advanced tooling beyond bronze-age metallurgy has been empirically verified, countering unsubstantiated claims of precision machining.

Evolutionary Links to Step and True Pyramids

The Layer Pyramid demonstrates late Third Dynasty (c. 2686–2613 BCE) advancements in step pyramid construction, utilizing an accretion layer technique where mudbrick courses were successively wrapped around a core, forming an estimated five to seven steps with a base of approximately 83.75 meters and original height of 42 meters. This method, evident in the visible horizontal and slanted bedding of surviving layers, built upon the stacked mastaba prototypes of earlier rulers, as seen in Djoser's six-step pyramid at Saqqara, to create terraced elevations symbolizing a stairway for divine ascent. Such layering facilitated incremental height gains while allowing integration of ramps or roadways atop each tier, reflecting empirical refinements in stability and scale during the dynasty's pyramid-building phase.

The Unfinished Northern Pyramid, attributed to the early Fourth Dynasty (c. 2613–2589 BCE), evidences the pivotal shift to true pyramids, with its excavated base measuring roughly 200 meters per side and traces of a planned casing slope near 52 degrees indicating an intent for smooth, seamless sides rather than exposed steps. Its deep bedrock-cut substructure, including a central pit descending over 20 meters to chambers lined in granite, parallels transitional designs like Sneferu's Meidum pyramid, where initial step cores were infilled with rubble and encased in fine limestone to achieve a true pyramidal profile. This evolution addressed aerodynamic and structural challenges of steeper, uniform inclines, as demonstrated by tool marks and control lines for casing alignment preserved in the pit walls.

Together, Zawyet El Aryan's monuments bridge Third and Fourth Dynasty innovations: the Layer Pyramid's rudimentary accretion underscoring persistent step-form reliance, while the northern structure's abandonment mid-excavation highlights logistical hurdles—such as quarrying precision and workforce coordination—in pioneering true pyramids, precursors to Giza's refined exemplars.

Scholarly Interpretations and Unresolved Questions

Proposed Builders and Chronological Debates

The Layer Pyramid at Zawyet El Aryan has been attributed to Pharaoh Khaba of the Third Dynasty (c. 2670–2650 BC) primarily due to a cache of stone vessels inscribed with his Horus name discovered in the vicinity during excavations. This attribution, first proposed in the early 20th century following Jacques de Morgan's work in 1896, aligns the structure with the transitional phase of pyramid evolution from mastabas to step pyramids, consistent with late Third Dynasty architectural experimentation. However, the absence of direct inscriptions on the pyramid itself or confirmatory royal annals has led scholars like Aidan Dodson to caution that the link remains circumstantial, potentially reflecting elite reuse of artifacts rather than definitive ownership. Chronologically, the pyramid's layered limestone construction and modest scale (base approximately 75 meters per side, surviving to about 17 meters high) place it firmly within the Third Dynasty's span (c. 2686–2613 BC), though broader debates on the dynasty's internal sequencing—exacerbated by fragmentary king lists and Palermo Stone omissions—complicate precise reign alignments.

In contrast, the Unfinished Northern Pyramid's builders and date evoke greater uncertainty, with proposals ranging from late Third Dynasty figures like Huni (c. 2637–2613 BC) to early Fourth Dynasty precursors, based on the site's deep subterranean shaft (over 30 meters) and lack of superstructure, suggesting an aborted project amid evolving pyramid designs. Excavations by Alessandro Barsanti in the early 1900s revealed no royal inscriptions, prompting Wolfgang Helck and others to reject ties to specific kings like Nebka or Baka, instead positing it as a experimental foundation from c. 2700–2600 BC, potentially contemporaneous with or predating Djoser's Step Pyramid at Saqqara. Chronological debates hinge on ceramic evidence and tool marks indicating Third-to-Fourth Dynasty transition, but limited access since the site's militarization in 1964 has hindered radiocarbon or stratigraphic refinement, leaving attributions speculative and reliant on comparative analysis with Giza's early pyramids. Empirical challenges include the Third Dynasty's compressed timeline (debated as 73–100 years), which strains accommodating multiple unfinished monuments without invoking co-regencies or usurpations unsupported by contemporary records.

Theories on Abandonment and Purpose

The Layer Pyramid, attributed to the Third Dynasty pharaoh Khaba (c. 2640–2630 BCE), is widely interpreted as an intended funerary monument, evidenced by its substructure featuring a sloping corridor descending to a rectangular burial chamber measuring approximately 3.63 by 2.65 meters and 3 meters high, akin to contemporary pyramids like that of Sekhemkhet. Supporting this purpose are adjacent mastaba tombs of elite officials containing artifacts such as ivory vases and seal impressions bearing Khaba's name, indicating burials clustered around the royal pyramid as per Old Kingdom custom. However, the absence of any interred remains, grave goods, or completed galleries within the substructure has fueled debate, with some scholars questioning whether the design anomalies—such as inconsistent shaft depths and an unfinished layered core—reflect a shift away from full burial functionality or experimental architecture during the transition from mastaba to pyramid forms.

Theories on its abandonment center on Khaba's likely premature death after a short reign, halting construction before the planned five-step structure (originally around 45 meters tall) could receive casing stones or internal completion, a pattern observed in other Third Dynasty projects. Alternative explanations invoke logistical or design challenges, as discrepancies in early excavations (e.g., varying reports of shaft depths by explorers like Barsanti and Reisner) suggest possible structural revisions or resource constraints amid Third Dynasty political instability, though no direct evidence of economic failure exists. Attribution debates, occasionally linking it to Djoser instead, underscore uncertainties but do not alter the consensus on funerary intent, derived from empirical parallels rather than speculative reinterpretations.

For the Unfinished Northern Pyramid, scholarly consensus holds it as a Fourth Dynasty (c. 2580–2560 BCE) royal tomb, inferred from its deep shaft (over 20 meters) leading to a burial chamber with an embedded granite sarcophagus oriented north-south, a feature aligning with early true pyramid complexes like those of Sneferu. Possible builders include Bikheris (a son of Khufu) or the lesser-known Baka, with the unfinished state—manifest in the exposed core and lack of superstructure—attributed to the prospective pharaoh's death before full accession or completion, preventing further work as successor priorities shifted. No artifacts or mummy were recovered, reinforcing the interruption theory, though the site's restricted access since 1964 limits verification, leaving room for chronological disputes placing it in the late Third Dynasty based on stylistic similarities to Khaba's pyramid.

Both structures' abandonment aligns with causal patterns in Egyptian pyramid-building, where royal mortality mid-reign (evidenced by short attested rules for Khaba and potential heirs like Bikheris) disrupted projects without evident sabotage or disaster, prioritizing empirical excavation data over unsubstantiated alternatives like intentional decommissioning. Their shared purpose as cenotaphs or tombs underscores the site's role in elite necropolis development, though unresolved substructure ambiguities highlight the need for future non-invasive analysis to test against biased early-20th-century reports prone to interpretive overreach.

Fringe Claims versus Empirical Evidence

Fringe theories about Zawyet El Aryan, especially the unfinished Northern Pyramid's subterranean pit, assert involvement of extraterrestrial intelligence or a lost pre-Ice Age civilization capable of advanced engineering unattainable by ancient Egyptians. Proponents, drawing from the site's military lockdown since 1964, interpret the T-shaped bedrock excavation—measuring roughly 28 by 14 meters at the surface and extending about 21 meters deep—as evidence of a concealed underground complex for interstellar travel or esoteric rituals, rather than a pyramid foundation.

These speculations lack supporting artifacts or inscriptions and rely on the site's inaccessibility to dismiss contradictory data, often amplified in social media and non-peer-reviewed outlets despite the absence of anomalous materials like non-local alloys or precision beyond copper-tool capabilities. In contrast, excavations prior to restrictions, including Auguste Mariette's 1825 discovery and Alessandro Barsanti's early 20th-century work, uncovered smoothed limestone walls, a descending passage, and granite elements consistent with 3rd-4th Dynasty construction techniques documented at Saqqara and Giza.

Archaeological dating places the Northern Pyramid's initiation around 2613–2494 BC, aligned with early 4th Dynasty pharaohs via architectural parallels to the nearby Layer Pyramid (attributed to Khaba, circa 2670 BC) and evolutionary step-pyramid cores using local limestone blocks without casing stones. Abandonment is empirically linked to incomplete superstructures and empty chambers, mirroring unfinished projects like Sekhemkhet's at Saqqara, likely due to a ruler's early death disrupting labor mobilization rather than technological failure or alternative functions.

Tool marks on the bedrock and associated quarries match those from Old Kingdom sites, producible by copper chisels, dolerite pounders, and ramp systems, as replicated in experimental archaeology; no evidence supports claims of powered machinery or non-human precision. The restricted zone's degradation, including post-excavation dumping, complicates re-examination but does not invalidate pre-1964 findings of dynastic pottery and mastaba alignments tying the site to elite Memphite necropoleis.

Modern Status and Research Challenges

Military Restrictions and Site Degradation

The Zawyet El Aryan archaeological site, located approximately 3 miles south of the Giza pyramids, has been designated a restricted military zone by Egyptian authorities since 1964, prohibiting all further excavations, geophysical surveys, and public access. This lockdown followed initial explorations by archaeologists such as Alessandro Barsanti in the early 20th century but ended systematic research abruptly, converting the area into a military base with ongoing operational activities.

These restrictions have directly contributed to site degradation through the overlay of modern military infrastructure, including bungalows and facilities erected atop the ancient necropolis, which have obscured and potentially compromised subsurface mastaba tombs and pyramid substructures. The lack of permitted conservation or monitoring has prevented mitigation of environmental factors, allowing unchecked sand deposition to bury remnants of the Layer Pyramid and Unfinished Pyramid, while the site's isolation has fostered unchecked vegetative overgrowth and structural instability in exposed elements. Without access for documentation or stabilization, original excavation shafts—such as the 30-meter-deep pit at the Unfinished Pyramid—remain vulnerable to collapse or infilling, diminishing opportunities for future recovery of artifacts or architectural data.

Egyptian military oversight, justified on national security grounds, has prioritized exclusion over heritage preservation, resulting in a de facto abandonment of the site's 3rd Dynasty features despite their proximity to more accessible UNESCO-listed monuments. This policy contrasts with intermittent allowances for photography or limited overflights but enforces ground-level prohibition, perpetuating degradation without empirical assessment or remedial action.

Recent Photographic Releases and Public Scrutiny (Post-2020)

In October 2025, rare historical photographs from Alessandro Barsanti's early 1900s excavations at Zawyet El Aryan resurfaced in popular media, depicting the site's extensive subterranean features and reigniting public interest. These images show a T-shaped pit approximately 30 meters deep, hewn directly into limestone bedrock and reinforced with precisely cut granite blocks, some measuring 4.5 meters long and weighing up to 8,000 kilograms. At the pit's center lies an oval vat roughly 3 meters long, 2 meters wide, and 1.5 meters deep, which reportedly held an unidentified substance prior to its emptying, though no chemical analysis was conducted at the time.

The renewed visibility of these photographs has amplified scrutiny regarding the site's inaccessibility, as Egyptian military authorities have restricted access since 1964, converting parts of the area into barracks and allowing debris accumulation that has degraded the ruins. This lockdown, imposed without official archaeological justification, has fueled speculation about concealed discoveries, with media outlets dubbing the location "Egypt's Area 51." Public discourse, particularly on platforms like podcasts, has questioned the absence of modern geophysical surveys or excavations, attributing the opacity to potential national security concerns or preservation efforts, though no evidence supports ulterior motives beyond standard military zoning near Giza.

Egyptologists maintain that the pit represents the foundational substructure of an unfinished pyramid, likely from the 3rd or 4th Dynasty around 2600–2500 BCE, consistent with nearby monuments like the Layer Pyramid attributed to Khaba. In contrast, independent researcher Derek Olsen has interpreted quarry graffiti reading "Seba" as evidence of a "gateway to the stars," suggesting advanced cosmic technology rather than funerary architecture, a view promoted in alternative media but unsupported by peer-reviewed analysis or contextual parallels in Old Kingdom inscriptions. The lack of sarcophagus or burial goods aligns with abandonment theories tied to dynastic shifts, not exotic functions, underscoring how sensational reinterpretations often overlook empirical stratigraphic and typological evidence from contemporary sites.

Prospects for Future Excavations and Preservation

The site's military designation since 1964 continues to preclude formal excavations, with Egyptian authorities maintaining strict access controls that extend to the unfinished northern pyramid and associated features. This prohibition, enacted amid post-independence security concerns, has halted fieldwork despite the site's proximity to Giza and its potential to illuminate transitional pyramid architecture from the 3rd Dynasty. Non-invasive methods, such as geophysical surveys, offer limited alternatives but require equivalent permissions, which have not been granted, rendering near-term prospects for substantive archaeological progress improbable absent policy reversals.

Preservation faces parallel constraints, as restricted entry impedes routine monitoring and maintenance, exacerbating exposure to groundwater rise, wind erosion, and unstructured debris accumulation reported in the substructures. The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities has prioritized high-profile sites like Giza for conservation funding, leaving Zawyet El Aryan reliant on ad hoc protections that fail to address long-term stability of the layered masonry and pit complexes. Collaborative international initiatives, potentially involving UNESCO or specialized geophysical teams, could enhance safeguarding through remote sensing and documentation, yet implementation depends on inter-agency coordination that has eluded realization for decades.

Gallery

Content generated by AI. Credit: Grokipedia

Megalithic Builders is an index of ancient sites from around the world that contain stone megaliths or interlocking stones. Genus Dental Sacramento